Here I offer some reflections around the on-going Urban Studies studio course entitled 'Activate: Fitness Urbanism and Its Misfits,' which I co-tutor with Helen Runting and Leonard Ma at the Estonian Academy of Arts. The studio course asks how 'fitness' produces value and subjectivity in the contemporary city. We state in the brief: 'As we enter the third decade of the 21st century, it appears that "fitness" is not only a quality demanded of architecture or its subjects, but of the urban environment itself. Through performance-based regulations, the doctrine of "active bottom" floors, and as armatures for the compulsive data harvesting of platform capitalism, cities are also "kept in shape" through policies laminated onto poorly articulated speculations about classless and genderless human subjects.'

In my previous post[1] I have looked at the concept of fitness in Ian McHarg, who extrapolated from Darwin’s biological meaning of the term referring to a genotype or population. Here I want to focus on a more common usage of 'fitness' referring to physical attributes of individual human bodies such as strength, endurance or, more elusively, being in shape. The impact of physical fitness industry on cities has caught the attention of urban commentators such as Richard Florida, who, with his love of hyperbole, described it[2] as 'the urban fitness revolution'. While Florida focused predominantly on the economic geography of gyms and fitness studios, that impact can be parsed in relation to the trend of remaking open spaces for physical fitness. Thus, in an interview[3] about the Underline project in Miami, a conversion of a strip of land under an elevated railway into a linear park, the architect James Corner explained that, compared to the widely known High Line, 'the Underline is more fast-moving. It’s about health and fitness, cycling, basketball, running and rollerblading. The similarities come from the ways in which we’re working to bring drama to the everyday and encourage people to spend time outdoors.' What are the premises for making such a claim?

The reference to Corner, the student and protégé of McHarg, is not accidental. Clearly he uses 'fitness' differently than his mentor, and yet, I want to suggest, the practice of Corner and his office Field Operation are representative of an influential strand in landscape – but not only landscape – urbanism, where the two meanings of fitness, biological and physical, become inextricable. In fact, Corner explicitly stated that 'a "fitness landscape" is ... both healthy (or physically fit) and synthetically symbiotic (or "fitting").' While Corner’s turn away from McHarg’s scientific pretence has been presented in terms of imagination (as the title of his collected essays[4] suggests), I think it is rather one that is steeped in certain neo-vitalist or (what the architectural historian Zeynep Çelik Alexander calls) 'neo-naturalist'[5] themes. Indeed, the above quote is from the essay[6] comparing landscape to 'life itself', which Corner understands in terms of resilience and self-organising complexity. I cannot dwell here on complex genealogies of these terms[7]except to point out how these neo-vitalist ideas justify a performative rather than critical approach to landscape design.

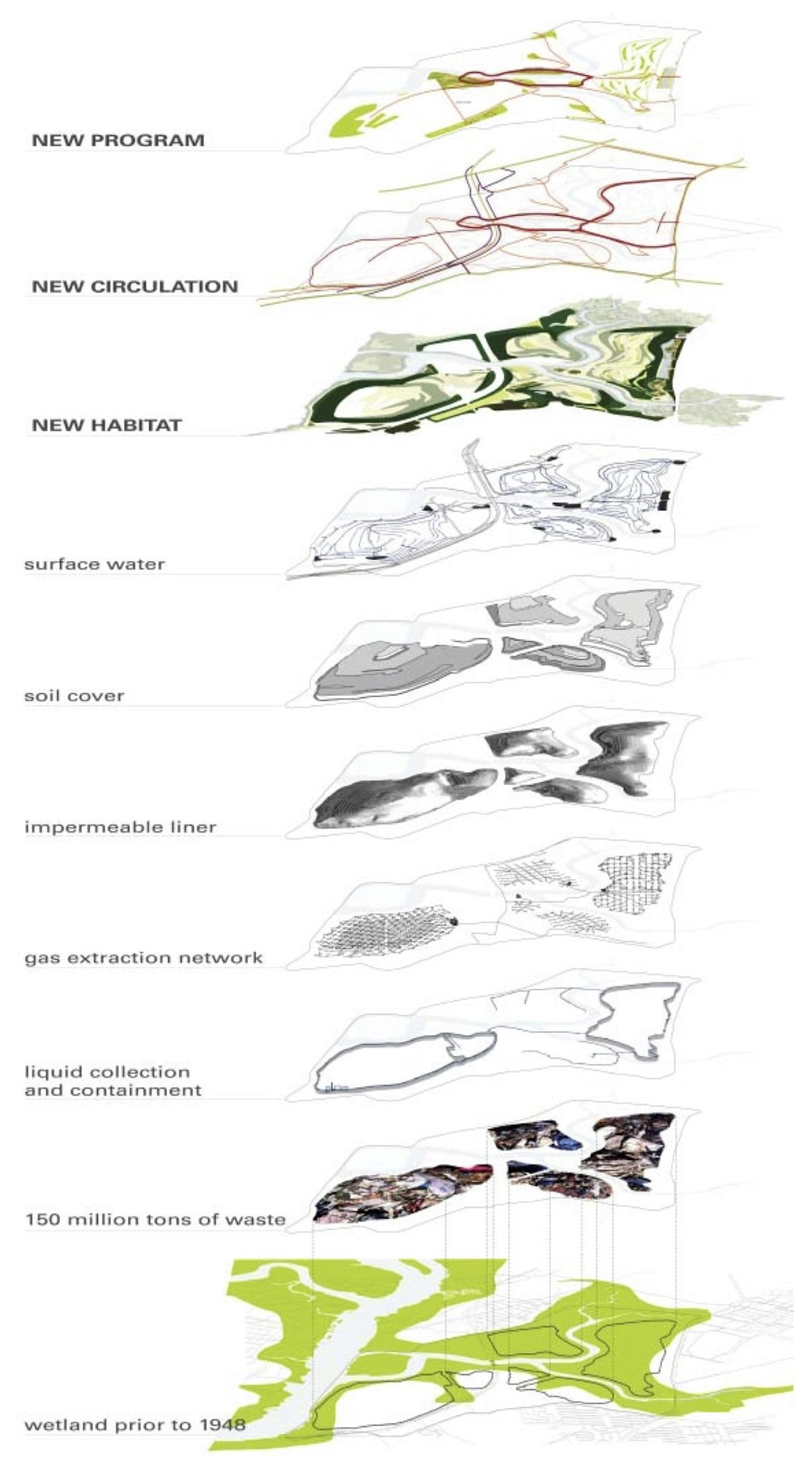

This can be parsed by considering Corner’s project for the reclamation and rewilding of Fresh Kills, the massive landfill located on New York’s Staten Island. Originally proposed with Stan Allen under the title Lifescape[8], it is a project complex in scale, duration and programmatic scope that extends over almost 10km² and three decades and seeks nothing short of spawning 'new forms of interaction between people, nature, technology and life.' The design is centred around a layering of programs that transforms McHarg’s map-overlay method into an instrument for effecting change. Mapping, Corner contends, is a creative activity: layers are not stacked to identify the least-cost/maximum-benefit solution, but rather extruded so as to diagram the production of new circulation networks, programs and habitats atop the existing layers of nature, culture and infrastructure. Layers are also extended in time so that the very process of change in natural and cultural ecosystems is incorporated as a factor in these diagrams, and horticultural techniques such as seeding, cultivating and propagating are invoked as metaphors for that change process.

In the end, however, little is said about the substantive goals of design, the values underpinning it, or the question whether, or how, the imagined change contributes or not to a better society. Rather change is evangelised for its own sake, and the measure of good urbanism is that in enables change. Corner challenged McHarg’s belief that landscapes have a single optimal state of 'fitness'. However, he went along with using and overextending other nature analogies in the urban field, conflating biophysical, political and behavioural change in nature, institutions and human subjects. Which brings us back to relations of power fabricated and occluded by the juxtaposition of biological and physical categories of fitness in the work of Corner and Field Operations. While further analysis would be needed to situate these relations within a broader set of post-Cold War transformations in capitalism and urban governance, and the New York mayoralty of Michael Bloomberg in particular, suffice it to conclude by stating that fitness landscape is not only a landscape that incorporates change as its own purpose, but also one that instils the ethos of change for change’s sake in users of that landscape.

Field Operations, FreshKills Park, Draft Master Plan: Illustrative View, 2006.

Field Operations, Freshkills Park Program. Draft Master Plan, 2006.

Freshkills Park, 2019. Photo: Maroš Krivý.

Comments