In urbanism we zone, we densify, we reorganise, we demolish, we rebuild… In all of this, cemeteries are one form of land-use that seem to be largely excluded from our indefatigable urge to transform. Even in frantic metropolises where the price of buildable ground continues to jump from peak to peak, the value of (garden) cemeteries goes beyond that of a simple ground for burial. Ideally they are as porous and open as the Aoyama cemetery in Tokyo or as culturally valuable as the Parisian Père Lachaise.

The latter houses 1 million departed and is only one of 14 intra-muros Parisian cemeteries. No long calculation is needed to understand that the number of deceased Parisians outnumbers the number of those alive (2.1 million), and this is probably the case for most metropolises – we live between our departed. And as our use of social media continually mirrors our real-life experiences, this process begins to manifest itself. In principle, platforms are based on interactions and communication: we post, we message, we like, we share; we produce data. So when we die, we don’t limit ourselves anymore to only leaving physical belongings behind, but also an ever-increasing amount of data. And with it, a certain perplexity of how to handle the latter.

In 2013, Google launched a feature named 'Inactive Account Manager' that enables users to specify what to do with Gmail messages or data from other Google services when an account becomes "inactive". Google’s fogged wording is paradigmatic for how most platforms avoid directly addressing the subject of death, not least because they were not created to do so. Similarly, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn and Snapchat focus on specific kinds of content, that is often ephemeral in character, and thereby not able to fully reflect all details of a person’s life.

Facebook, on the contrary, organises content around a timeline, encouraging users to add from all aspects of their biography: education, work, interests, views, relationships… This made it the most popular social media platform, with 2.70 billion monthly active users as of mid-2020, voluntarily or not, and an ideal place for mourning. Initially, Facebook profiles of deceased could either be deleted or frozen (cremated or embalmed). But with a steadily amount of users departing real life, Facebook had to increasingly address the subject of mortality and its related ethics in a more nuanced manner.

Until now, when someone passed away, we offered a basic memorialized account which was viewable, but could not be managed by anyone. By talking to people who have experienced loss, we realized there is more we can do to support those who are grieving and those who want a say in what happens to their account after death. [1]

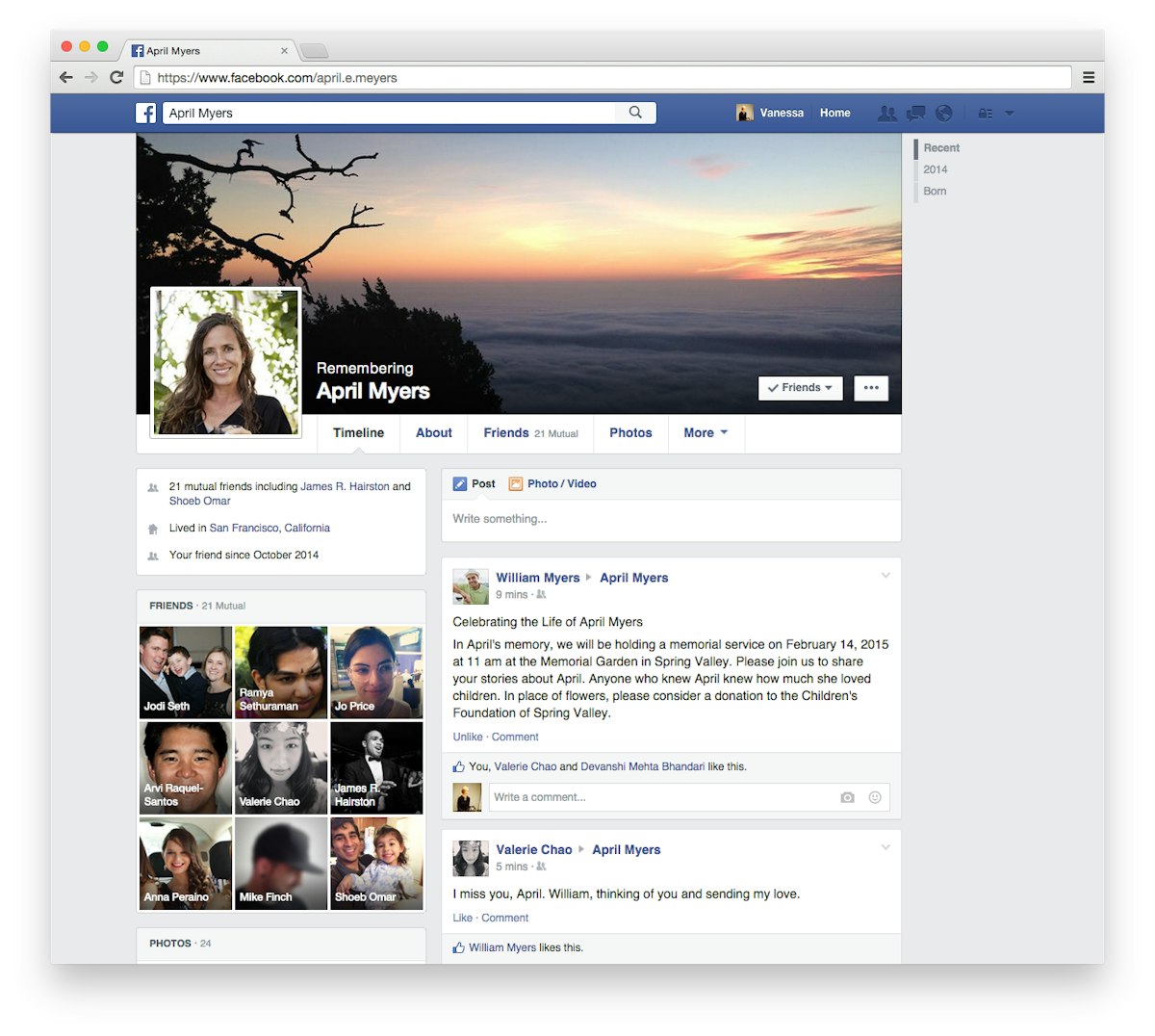

In 2015, the above statement accompanied the introduction of a new feature allowing an account holder to designate a 'legacy contact'. Once a fatality is communicated and proven to Facebook, this designated family member or friend is able to write a post to be displayed at the top of the memorialised profile, update the profile picture, and cover photo of the deceased, and even respond to new friend requests. This legacy contact is a sort of digital master of ceremonies and not least, a curator of the digital archive of the deceased user.

A memorialized Facebook timeline

A memorialised Facebook profile can be understood as a digital tombstone, with predefined dimensions for a photo, message or piece of funerary art. Regardless of which funeral rites the religion or culture of a deceased person would imply in real life, online, these rites require translation and reduction to match the digital format. This implies a globalisation, standardisation and unification of these memorials. From Facebook’s perspective, this also means that an active user profile turns into a passive page, whilst also a place for gathering online. This fact is essential, as it generates traffic and thereby a financial interest to keep a dead person's profile online. When, in 2019, Facebook added a new 'tributes section' for memorialised profiles, it revealed that 'over 30 million people view memorialized profiles every month to post stories, commemorate milestones and remember those who have passed away.'[2]

Until the mid-2010s, talking about death on social media was still an anathema. Sharing death on platforms was experienced as a truly uncomfortable interruption of the eclectic daily content feed, both for those sharing it, and those reading it. The rise of social media was driven by the desire to share one's life and to learn about those of others. Yet life is inseparable from death, and it was only a matter of time until this subject needed to be added to online communities. When the iconic like button was introduced by Facebook in 2009, it indirectly disciplined users to share something likeable(or at least agreeable). Thereby, Facebook had consciously avoided becoming a platform for negativity, but also has excluded certain aspects of our lives from the social network. Only in 2015, Mark Zuckerberg evoked that an eventual 'dislike' button could allow for the the expression of empathy in those cases when a like seemed insensitive on a specific post.[3]

Not every moment is a good moment. If you're sharing something that is sad, whether it's something in current events, like the refugee crisis that touches you, or have a family member passed away, then it may not feel comfortable to like that post, but your friends and people want to be able to express that they understand and they relate to you, so I do think it is important to give people more options than just to like as a quick way to emote and share with their feeling on a post.

Facebook did indeed never release the infamous dislike button, but finally opted for a set of five types of reactions: love, haha, wow, sad, and angry. This, differentiation could as well have emerged from observing the reactions of their users towards certain types of news, and the evolution of the Facebook algorithm in displaying these reactions. A 2019 study[4] titled 'Cross-national evidence of a negativity bias in psychophysiological reactions to news', concluded that the prevalence of negative news content lies in the tendency for humans to react more strongly to negative than positive information: 'Negativity biases affect news selection, and thus also news production.' Death, undeniably is bad news and even more importantly nostalgia – the most powerful secret weapon of marketing – is a form of mourning.

With millennials losing interest in Facebook, will the platform become a place for the dead rather than the living? What options will be available to interact with (and eventually even animate) our digital remains? Will users be offloaded when they don’t generate sufficient online traffic? May globally accessible virtual memorials, make local physical memorials obsolete?

Comments