The concept of TDR (Transferrable Development Rights), popularly known as Air Rights, originated in the United States, in connection with zoning. One key idea is that development rights are attached to land parcels depending on their uses and zoning, specifying both volume and heights of structures on the parcel. At times, for certain purposes, such as historic preservation or public uses, these rights are transferred from one parcel to another, becoming transferrable development rights or air rights. Air rights have played a key role in the vertical development of many cities, most notably New York. In Mumbai, the concept took on a perverted form. From the 1960s when the first development plan was drawn up for Mumbai, until the 1990s, development rights were uniform across most land parcels. This led to the constriction of development and density, leaving the city with an enormous shortfall in housing even as migration into the city increased exponentially.The gap was filled mostly with informal, or rather self-built housing that used vacant land parcels wherever available. In the 1990s, eager to develop more housing, both for people in self-built housing as well as for more affluent citizens, the state created a formula to multiply air rights by attaching them to the number of people moved out of informal housing. Rather than transferring the development rights attached to the land parcel by virtue of its location and zoning alone, additional air rights accrued to the parcel simply by virtue of the number of people occupying the land.

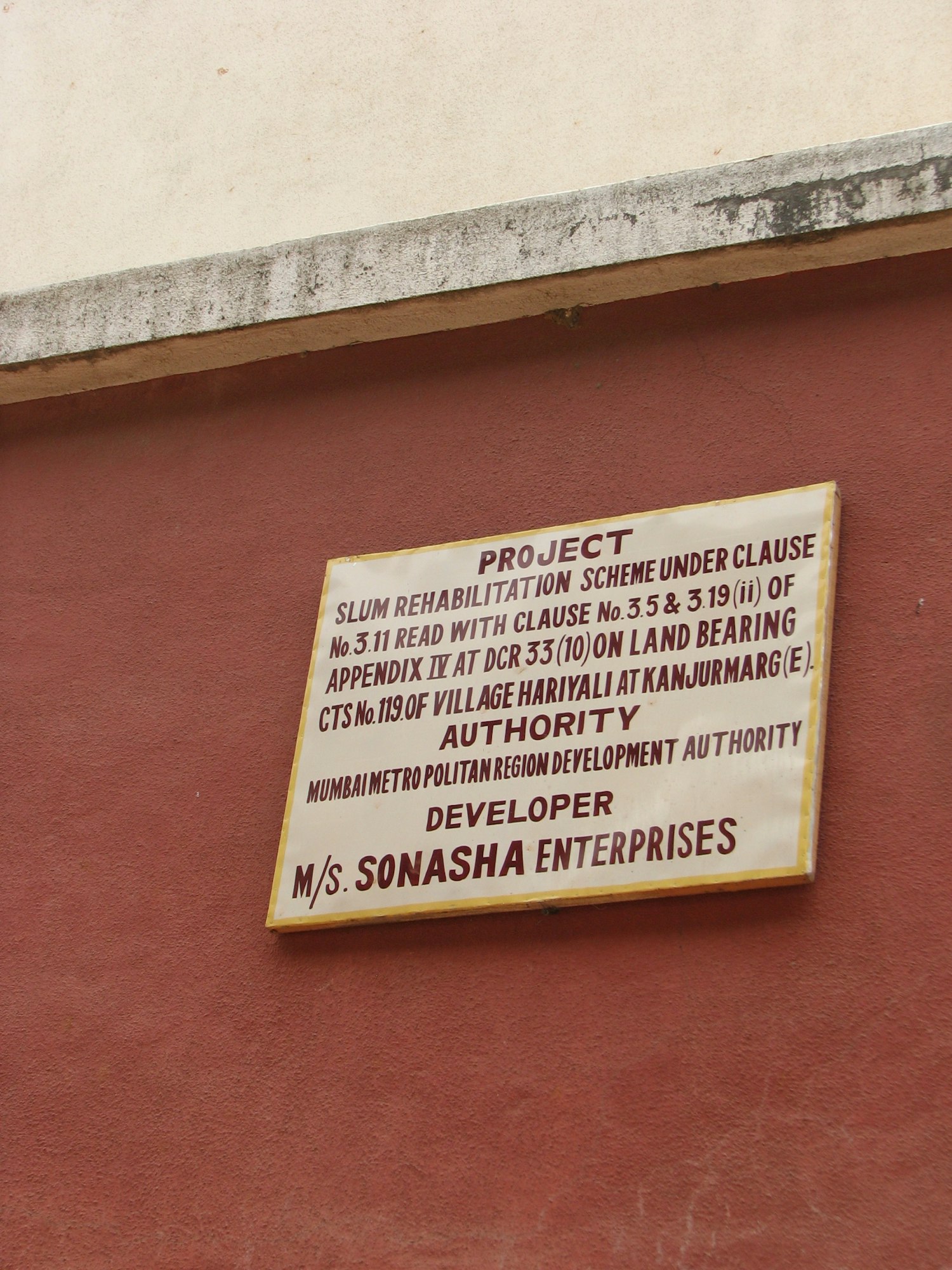

If, by the standard calculation, a land parcel might generate one thousand square feet of development potential, by producing a standardized dwelling of 225 square feet for each existing occupant of the land, the developer could claim roughly half that amount (or roughly 115 square feet) for each current occupant, resettled into the standardized dwelling unit. Current occupants could be classified as slum dwellers, tenement dwellers or occupants of ‘dangerous buildings,” that were prone to collapsing due to neglect and poor maintenance. These dangerous buildings, generally located in the older neighborhoods of Mumbai were also often buildings that had been subjected to rent controls, leading to abandonment by their owners. Further forensics reveals that each case of air rights generation and usage could have its own peculiarities. In some cases, current occupants are moved off site and resettled elsewhere while the air rights they generate are used in situ whereas in other cases both current occupants and air rights are moved elsewhere. In yet other cases, both the air rights and the current occupants are resettled on the original parcel, leading to extremely peculiar urban morphologies and topographies.

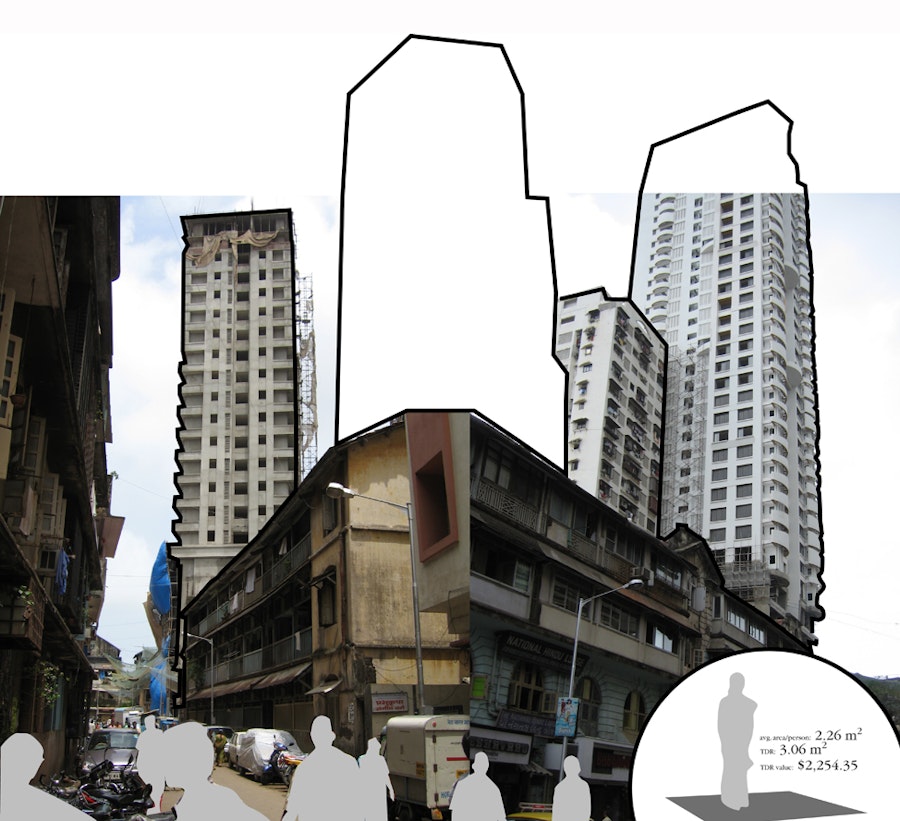

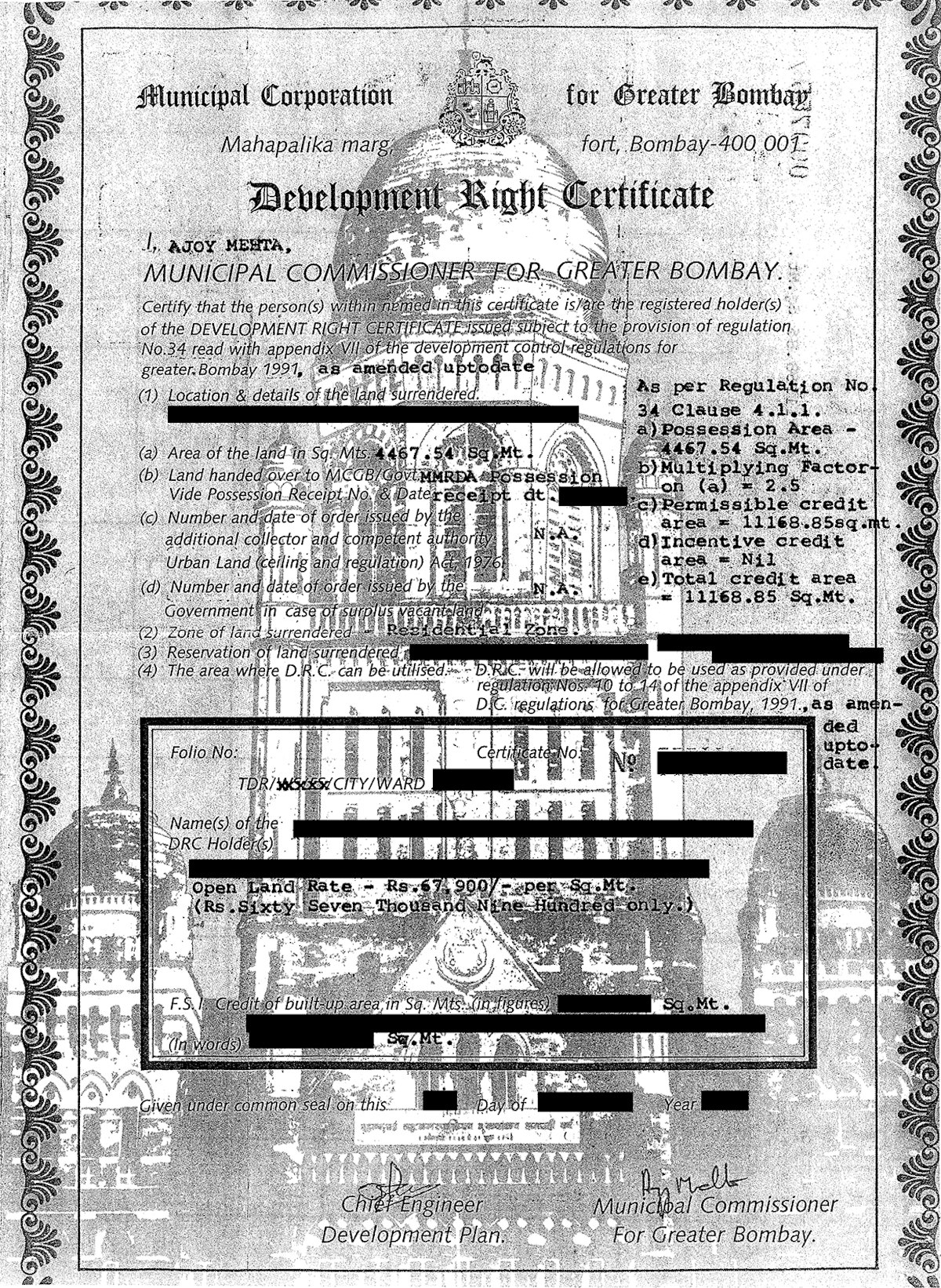

These formulae allowed tiny city plots to generate many multiples of their allocated development rights as air rights, leading to super tall towers clinging precariously to narrow lanes and collapsing infrastructure. Here, the attachment of air rights to the dis-placement and circulation of persons rather than to places or parcels of land leads to a decisive convergence between society and economy, appearance and value, person and thing, generating new ways of living and being urban. This exchange between person and development right is the de facto work of the platform before its digital avatar. The TDR certificate issued by the Municipal Council of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) is the legal tender on this platform while the coin of circulation is the displaced citizen, moved out to cash in on the site’s potential to generate profit and accumulate capital. The issue and use of this legal tender has permanently split the governance of the city between public and private interests, creating deep uncertainties about how the urban environment might transform and whose interests will prevail in those transformations. The circulation of these certificates, their sale and exchange takes place across opaque networks but might be forensically traced back from the built forms and environments that it enables. Platform thus connects person to space and building to documentation and displacement, managing its volatility through strategic distribution of air rights where required. However, this platform is virtual and analog, rather than virtual and digital. Encoded into certificates issues by the Municipal Corporation, TDR is locked into steel cupboards and iron safes, its existence is sometimes pure conjecture fueled by rumor and its calculation keeps changing based on the numbers of people being displaced in the city to generate air rights as well as based on the number of parcels being acquired for various purposes by the civic administration.[1]

Fig. 2 Air Rights Transfer Representation. Artist: Colleen Macklin

Fig. 1 Original TDR Certificate, Redacted. Source: Anonymous Owner

Fig. 3 Slum Rehabilitation Scheme Notice. Photo: Vyjayanthi Rao

Comments