In Pittsburgh in the 1970s, architectural and scientific sensibilities converged in the construction of a computational understanding of the city. The early experiments in computer-aided urban design at the Institute of Physical Planning at Carnegie Mellon University are illustrations of this phenomenon. They indicate a fledgling view of the urban as a computational entity, and of design as an overarching, supra-disciplinary concept.

In the late 1960s, when Carnegie Tech and the Mellon Institute of Research merged into a university, a new School of Urban and Public Affairs (SUPA) was created with the mission to 'deal in a scientific manner with problems of the public sector' and help build the 'civil-industrial complex.' Funded by gifts from the Richard King Mellon Trusts and the Aluminum Co. of America, this school sought to bring together disciplines such as political science, anthropology, sociology, and urban planning to address issues of public administration and – crucially – urban renewal. The Institute for Physical Planning (IPP) was one of three research centres started within the school under the leadership of the late architect and computer scientist Charles M. Eastman. Members of the IPP worked on surveys and planning research in public housing studies, but they soon began to focus on loftier ambitions related to the application of computing to architectural and urban representation and 'problem solving'. We may see the IPP as a disciplinary intervention designed to transform architectural and urban disciplines through computation, supported by a new curriculum and by the establishment of a doctoral program 'to promote more rigorous methods in architecture'. The IPP was thus aligned with the intellectual makeup and industrialist ethos of the newborn university.

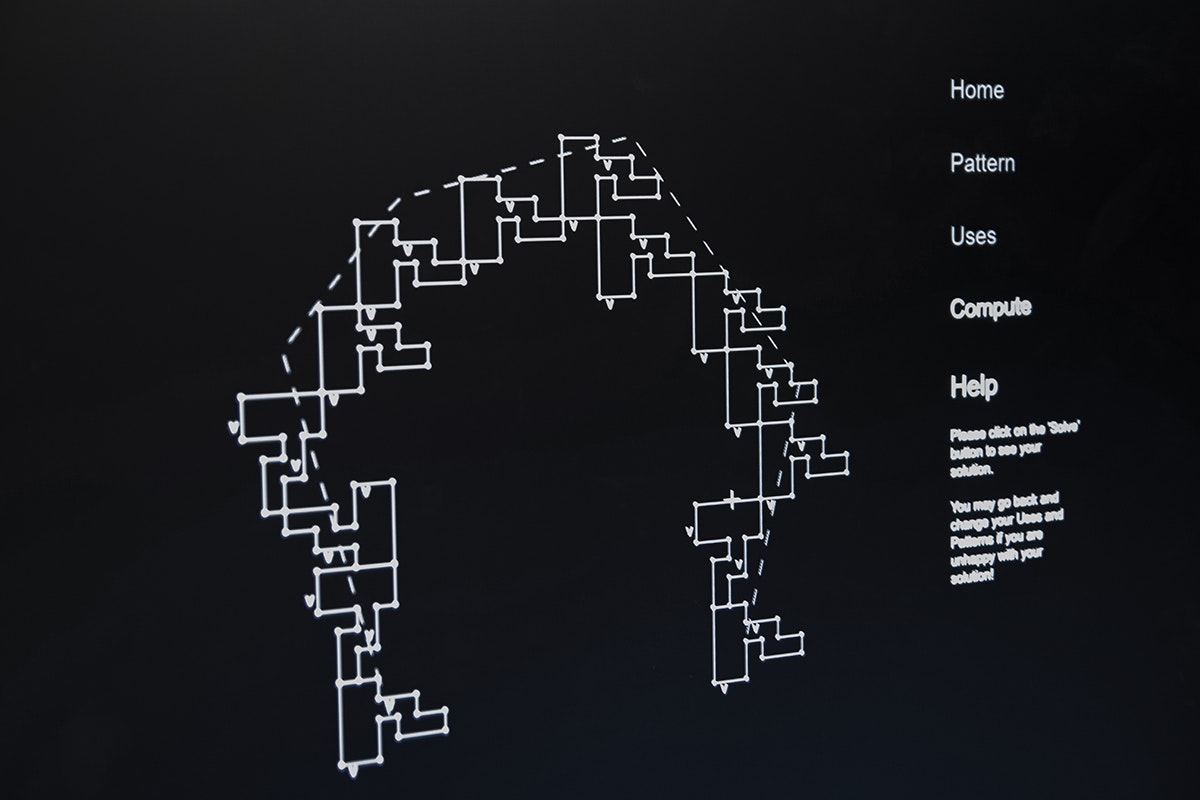

Patient zero of this experiment in architectural scientism was Charles Eastman's Ph.D. student Christos Yessios, whose 1973 dissertation was co-advised by prominent computer scientist and early AI researcher Alan Newell and supported by NSF funding for 'the development of formulations and algorithms for spatial arrangement problems and the analysis of hierarchical problem solving'. Yessios formulated one of the earliest examples of computer-aided urban design, CISP, a problem-oriented programming language for site planning built on FORTRAN. Referencing Chomsky's 'generative grammars', Alexander's 'pattern languages', and more immediate ideas about AI and design as problem solving techniques developed at CMU by Newell and Herbert Simon, Yessios followed a 'linguistic model' for computer-aided site planning that, on the one hand, specified a repertoire of units and, on the other, established rules for their computability. CISP, which was never implemented, allowed users to specify a repertoire of units for site planning and establish constraints such as views or access points. Using a backtracking algorithm, the system iterates through alternative placements of the units until it finds a solution that satisfies the constraints.

If software systems can be seen as artefacts embodying theoretical commitments about the practices they are meant to support, CISP was the opening salvo of a computational theory of urban design. The types of operations enabled by CISP are greatly simplified versions of even the most elemental of urban design operations. And yet, the translational work they performed between computation and urban design – the inscription of design as a series of machine operations – made CISP a legitimate expression of what was to become a dominant mode of knowledge production. Aligned with contemporary AI discourse, its operative logic construed design as an algorithmic 'search' through a combinatorial space governed by rules and constraints. Experiments like CISP were expressions of a colonising impulse typical of computer cultures. While thematically linked to urban concerns, the view of architectural and urban design that emerged was more in line with information processing discourses than with Pittsburgh's specific urban challenges. These are, perhaps, the perks of abstraction.

In this context, the word 'design' also started to gain a new meaning as a kind of general problem solving which, when formalised mathematically, could exist anew in the symbolic worlds of software. Here, architecture and the city were understood as a special instance of a larger category of 'physical systems'. In this new arena, data structures and building structures were parallel means of constructing – a rhetorical alignment which was central to the work of the group. These researchers' theoretical frameworks (AI, cognitive science and psychology), and methodological inclinations (protocol analysis and computer language building) equated humans and computers as cognitive, symbol-crunching machines.

Meanwhile – and foreshadowing present-day 'smart-city' discourses – the city started to appear as an information processing machine.[1]

Comments