At the dawn of democracy in South Africa in 1994, there was a societal consensus that a large-scale national housing programme was needed in order to mark a break with the racialised history of public policy. By addressing the 2.3 million housing ‘backlog’, the state could achieve a number of important developmental goals that could make a material difference, while at the same time reinforcing its own legitimacy. The developmental rationale ran along these lines: public housing would provide an asset for the black population that had been economically disenfranchised by apartheid legislation which prevented land ownership in cities combined with exclusion from skilled employment opportunities ensured by a deliberate rigging of the education system. Combined with land tenure security, this asset would begin a multi-generational process of reversing this legacy. Furthermore, a large-scale housing programme would generate much needed employment and potentially even grow a new class of black-owned construction and civil engineering companies that could be enrolled as the implementing contractors, reversing the monopoly of large white-owned companies. In these senses, an aggressive public housing programme would be a symbol of restitution, redistribution and empowerment.

By 2000, after five years of relentless implementation of the programme, a massive impact was registered. According to official records, the government had processed almost 1 million housing subsidies. These subsidies covered the full costs of land, a 32-square-metre free-standing house and internal wet services for a toilet and kitchen. Connective infrastructure was covered by other subsidies. The cost of each subsidy is presently around $10,000. According to public sources, the delivery rate of this programme reached 3.3 million units by 2019. Over the years the programme evolved not only to address the provision of public housing for income-poor households, but also to facilitate access to affordable rental housing, to upgrade informal settlements, and more recently, to enforce provision of classic site and service projects for new migrants in urban areas. This expansive public housing programme is of course an impressive achievement, and is certainly the envy of many social democrats who believe in housing rights.

However, a substantial body of scholarship and policy critique questions the aggregate impact of the programme, especially if considered from a spatial justice perspective. I’ll attempt a brief explanation at the risk of simplification. Since the housing subsidy amount did not keep pace with inflation, and the minimum standards of public housing went up, the only way in which the programme could be sustained was to supply public housing on the cheapest land; this meant on the periphery of cities and towns. These greenfield locations were typically devoid of other economic and social infrastructures such as markets, schools, public space, clinics, public transport, commercial infrastructure and so on. This meant households were cut off from urban opportunities and social networks as soon as they took occupation, engendering a number of governance challenges because criminal gangs favour operating in mono-functional voids. At a city scale it meant that the public-housing programme exacerbated racialised class segregation between the ‘townships’ and the ‘suburbs’. Since economic value aggregates in suburbs and commercial/industrial areas, those living in new public-housing schemes were further excluded from easy access to economic opportunities. It is impossible to overstate how significant this is when considering the current context in South Africa, where unemployment is well above 30 percent for black populations, and more than 50 percent of black households subsist below the income poverty line.

To add insult to injury, the so-called ‘asset’ also immediately depreciates as can be gleaned from the informal resale market for this class of housing. As mentioned above, the cost of provision is around $10,000 but resale prices could drop as low as $2,000 because residents are desperate for cash income, and from a livelihood perspective it makes more sense to access the cash, move back to an informal settlement and participate in informal economic life there. Even though systematic research into this phenomenon is in short supply, it is a significant minority that pursue this route. For those who stay, the vast majority invest in erecting informal settlement structures on the plot, sometimes up to five, but more typically three (Figure 1 provides a visual sense of public housing and backyard shacks). These shack structures then become a form of rental income. As a result of this phenomenon, new townships comprised of public housing very quickly treble densities, placing an enormous strain on infrastructure systems that were not designed to take this process into account.

Figure 1: Andy Mkosi & ACC. Formal and informal housing interspersed, Du Noon, Cape Town.

Nationally, almost 21 percent of households are in informal settlements, and up to 40 percent of the total are not in freestanding informal settlement areas but rather in ‘backyard shacks’, as they are colloquially called (figure 2 provides a sense of a typical informal settlement community with freestanding shacks). Since backyard shacks are not recognised or regulated, tenants are of course vulnerable to exploitation and have access to limited public services, especially the free lifeline subsidies that municipalities provide to ensure some access to water and electricity. There seems little chance of the ‘backyard phenomenon’ improving because the landlords cannot access finance to improve the quality of the structures, and as long as they don’t have access to affordable finance, they cannot incrementally improve the quality of the dwellings or the collective space that glues them together. An underlying reason for such market failure is a widespread practice of redlining by commercial banks when it comes to the townships.

Figure 2: Alexia Webster & ACC. Informal settlement in Khayelitsha, Cape Town.

Cue a platform urbanism innovation in Johannesburg, supported by the Gauteng Provincial Government. Inside of a special programme that seeks to grow economic activity in townships (where the majority of residents live), an ambitious initiative is underway to address regulatory blind spots and market failure when it comes to backyard shacks. This programme asked, how can affordable finance be extended to homeowners who have a number of shacks on their property, so that they can replace them with a 2-3 storey stack of apartments that can provide rental opportunities and commercial space for micro enterprises? Furthermore, how can risk be minimised for these typically unbanked homeowners so that they can gain an appreciating asset in the shortest possible time? How can these rental units be supported with a digital platform similar to Airbnb to ensure that the spaces are constantly occupied but also subject to customer reviews? The programme also tried to figure out how design and construction expertise can be pooled so that new structures are soundly built with minimal maintenance requirements and primed for green infrastructure technologies, especially decentralised renewable energy grids. In this regard, the programme wanted to ensure that construction will be done using local labour and small contractors that are rooted in the same communities. After extensive consultations, negotiations, design labs, modelling and institutional design, a pilot was launched in 2019 in an established township called Thembisa, in Johannesburg.

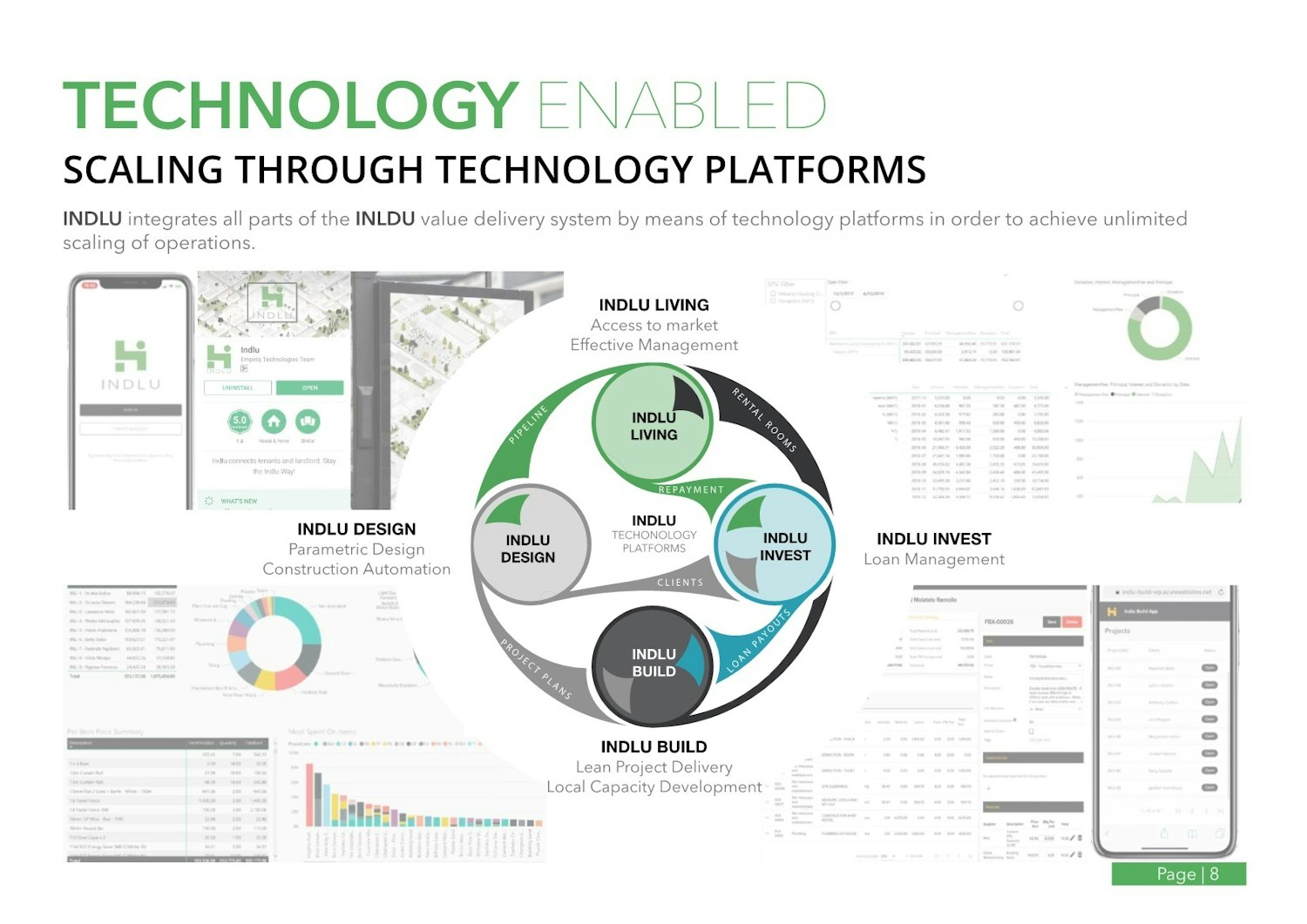

At the core of the initiative is an implementation agency called Indlu Urban. It implements the programme on behalf of a public-private partnership (PPP) between the Gauteng Provincial Government and Melana Housing Developments which is administered by the Bophelo Social Fund. The social impact PPP was formally established in December 2020 but the initiative has been in extensive experimentation since early 2019. An important and vital dimension of the program is that it adopts a precinct-level perspective instead of simply working with individual landowners. It also strives to understand the full value chain of planning, design, finance, construction, property management, repair and maintenance with an eye on localising employment and business opportunities. It is both complex and elegant and strives to make the ultimate user experience as seamless as possible. Two users are kept in mind: the landlords seeking tenants and the prospective tenants themselves. They are connected via a technological platform that will provide information about rental opportunities for prospective tenants, the state of loan repayment based on income received and project management capacity, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Components of the technological platform underpinning the Indlu Urban Initiative.

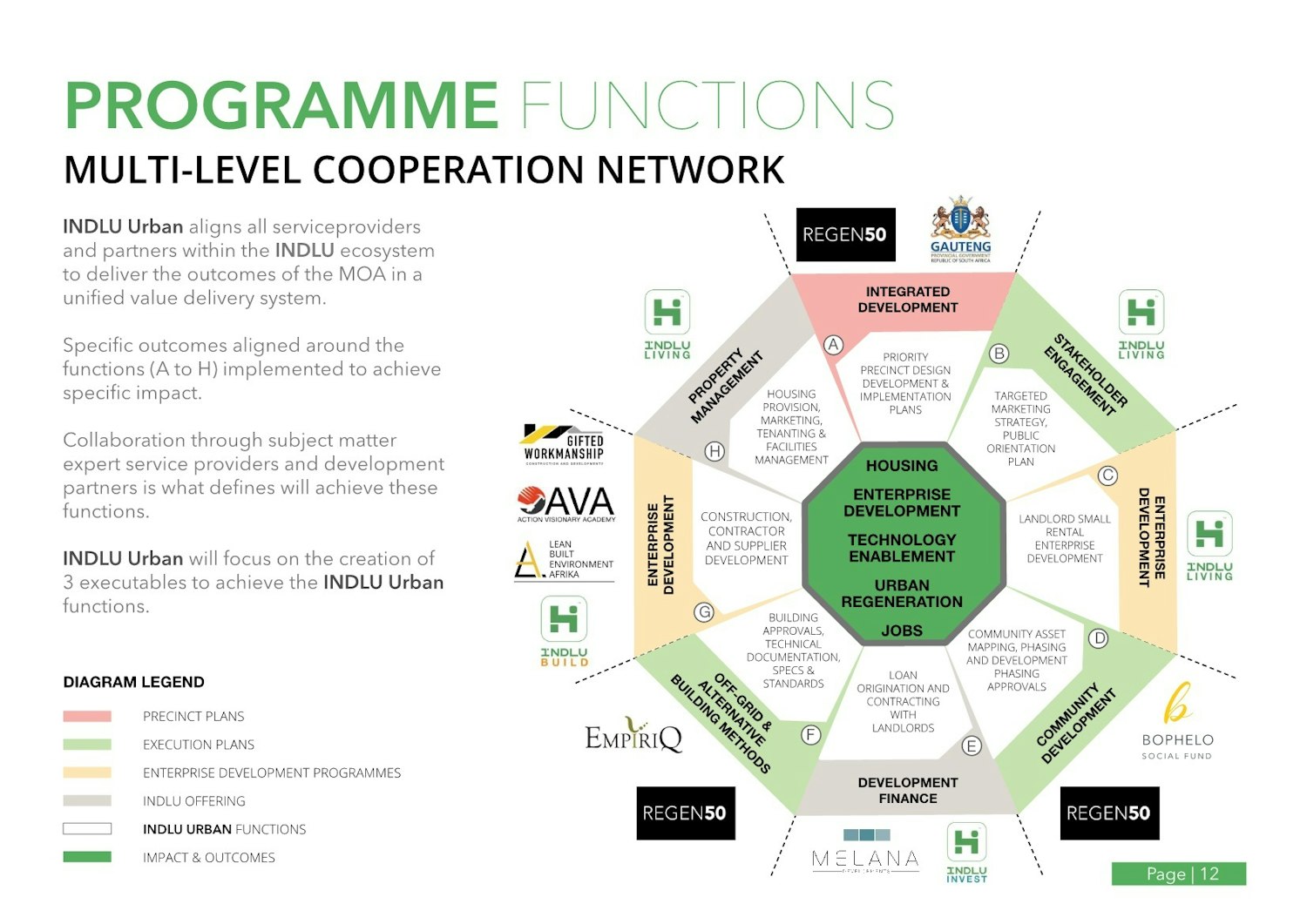

The investment in digital platforms is crucial because of the number of specialist agencies that have to be enrolled to ensure that the programme can succeed despite the many moving parts, and the complete lack of precedent, even though it involves such a large number of households. The institutional ecosystem is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Implementation entities for the different elements of Indlu Urban Initiative.

In my recent correspondence with the lead public officer driving the initiative from the Gauteng Provincial Government, he informed me that one of the metropolitan governments adjacent to Johannesburg, the City of Ekurhuleni, has decided to implement the initiative in one precinct in 2021. However, when the Banking Association of South Africa was engaged, they found the risk profile of the initiative unpalatable at present. This is a sober reminder that though digital platforms may have the potential to create compelling new models of development that are simultaneously more inclusive, productive, efficient and consistent with principles of interning value in marginal communities, they do not guarantee a shift in prejudice or systemic exclusion. The only remedy for this remains political mobilisation, oppositional tactics and exposure of encrusted privilege.

Comments