[T]he ‘Sand-Man’ who tears our children’s eyes … This fantastic tale begins with the childhood recollections of the student Nathaniel: in spite of his present happiness, he cannot banish the memories associated with the mysterious and terrifying death of the father he loved. On certain evenings his mother used to send the children to bed early, warning them that the ‘Sand-Man’ was coming … ‘He is a wicked man who comes when children won’t go to bed, and throws handfuls of sand in their eyes so that they jump out of their heads all bleeding. Then he puts the eyes in a sack and carries them off to the moon to feed his children. They sit up there in their nest, and their beaks are hooked like owls’ beaks, and they use them to peck up naughty boys’ and girls’ eyes with.’ Freud, The Uncanny, 32

Smart Dust consists of sensors at the nanotechnology level that can be deployed in the millions to billions, with a myriad of applications. Smart Dust is both the ultimate instantiation and the ultimate nightmare for IoT. “Smart Dust – The Future of Global IoT”, forescout.com, 30 August 2017, emphasis added

It is blind hubris to think that a deus ex machina is always just around the corner, outsourced, or just above the stage ready to drop at the push of a button to save the day like a super-hero loner, naively or deviously bypassing the plot’s context and complexity. It is the archaic Kubernetes transferred to a voracious cybernetic numeracy supported by an enchanting ‘machinic’ fetishism which is leading me to these transversal reflections on digital platform capitalism and their power overlords. I borrow from McKenzie Wark’s pivotal discussion about the existence of a new elite class at the top of the class hierarchy, the vectorialist class, corresponding to a new vectorialist mode of production and connected to new class relations derived from the monopolistic commodification of information. Mark Poster’s 1990 Mode of Information is an important early attempt to understand electronically mediated communication, but of course could not completely envision the explosive growth and dominant power of this new mode that is the object of Wark’s piercing inquiry, now even more aggressively dominant due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Wark’s argument empirically and theoretically describes what is now happening on a global scale in the sociopolitical, cultural and economic arenas between a new hacker class producer of information susceptible to be enclosed and commodified and a powerful vectorialist class which ‘owns and controls the vector ... to describe in the abstract the infrastructure on which information is routed, whether through time or space’.[1] This hidden and overt struggle forces us to expand our understanding of what capital and capitalism is at the present time, examining whether we can still call this era ‘capitalism’. In this way Capital Is Dead. Is This Something Worse? challenges us to think outside the box of capital as essence and even beyond capitalist realism to make room for other words and other worlds, where of course the jury is still out, ergo the question mark.

The accelerationist digital rampage under COVID-19 and the staggering accumulation of wealth in the first year of the pandemic added more than half a trillion ($540T) US dollars to the bounty of the 10 richest men in the world. Oxfam International’s 2021 Report ‘shows that COVID-19 has the potential to increase economic inequality in almost every country at once, the first time this has happened since records began over a century ago. Rising inequality means it could take at least 14 times longer for the number of people living in poverty to return to pre-pandemic levels than it took for the fortunes of the top 1,000, mostly white male, billionaires to bounce back.’[2]

It is a sobering X-ray of the present condition of economic enclosures and externalities, benefiting a staggering few, whom I would call ‘neo-feudal’ lords or ‘techno-feudal’ (Yanis Varoufakis) lords, since all avail themselves in one way or another of a massive global ‘enclosure of the commons’ through digital platforms. True, ‘feudalism’ is a retro view, but, in a kind of Guattarian transversality, I see it here partly as an aesthetic of power, a style, in the manner of the ‘lordly’ behaviour of these vectorialist platform owners and financiers, but also because it describes a new/old form of neo-colonial ‘possession by dispossession’ (David Harvey), where an absolute concentration of exponentially growing power and wealth is vested in what is literally a mere handful of individuals.

Neofeudal and neomedieval ideological, political, economic, and technological theorisations and characterisations can be found in Isaiah Berlin’s mid-twentieth century discussion of a kind of ‘neomedieval romanticism’, Hedley Bull’s 1970s neo-feudal political architectures, Stephen J. Kobrin’s 1998 ‘Back to the Future: Neomedievalism and the Postmodern Digital World Economy’, Rajesh Bhattacharya and Ian Seda-Irizarry’s ‘Problematizing the Global Economy: Financialization and the “Feudalization” of Capital’, and Anand Giridharadas’ ‘new feudalism’, to name a few.

Nineteenth-century ‘gothic’ literature kept alive the romantic, philological, and uncanny elements of a real and an imagined popular culture Christian medievalism, which about a century later would be revisited by, among others, the acclaimed Italian novelist and semiotician Umberto Eco, and of course Lord of the Rings and Star Wars, the ‘medieval’ villain Lord Darth Vader and sundry other overlords. In fact, there continues to be a particularly active attraction to medieval, gothic, and occult themes in films, songs and novels, not only in the West but also in China, Japan, and South Korea, for example, where medieval epics, spiked with martial and magical arts and Taoist, Buddhist, Confucian and/or Shinto ethics and aesthetics are popular.

Exploring this secular fascination with magic and the political exploitation that power conjures up from this fascination is in part what Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment is all about, as is Furio Jesi’s macchina mitologica. They confront the apparent paradox of a disenchanted secular world (Max Weber) and Émile Durkheim’s sociology infused with a Nietzschean ‘death of god’ hermeneutics while continually reverting to the re-enchantment of myth and/or the nationalistic ‘Volk’ narratives so dear to fascism and neofascism. This recursive state of affairs, where ‘myth is enlightenment and enlightenment already myth’, is beneficial for the status quo and its entertainment-desire machine, and, as a key pedagogical, political, and ethical concern of the Socratic trio, was already present at the dawn of Western thought.

This mass popularity, however, should not distract us from exploring further the brutal feudal-like ‘shadow’ side (Jung) of these rapid and complex capitalist transitions. While such popular ‘medievalism’ does seem to hark back to some kind of longing for a heroic time when things were not merely transactional and instrumental, this fandom may obscure or even help naturalise a highly toxic ‘neofeudal’ state of affairs. So I would like to briefly look back and forward and to the present, channelling the gaze of Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History, in order to ‘collage’ that backward gaze with Warks’ gaze, and Hoffmann’s gothic tale, via Freud, to graft, superimpose, a ‘neofeudal’ moniker onto the hybrid that is digital platform capitalism today, which of course could not care less how it is named as long as its juggernaut keeps on delivering its exponential super-profits and power grabs.

This is how in this COVID-19 lockdown angst and vein of overlapping inquiries, during the last months of 2020, I decided to revisit Freud and his interpretive influence over generations of thinkers, activists and practitioners, looking for inspiration and/or potential guidance for this essay. My engagement with one scholar always leads me to a pedagogical village and an ecology of knowledges and stories. In this case, I found myself simultaneously reading Elisabeth Roudinesco’s insightful Philosophy in Turbulent Times along with her acclaimed recent Freud biography, E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class, some chapters of Carl Jung’s Alchemical Studies, Mysterium Coniunctionis, Marie Louise von Franz’s Aurora Consurgens and the Interpretation of Fairy Tales, Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, and the letters exchanged between Carl Jung and the Austrian quantum physicist Wolfgang Pauli on cosmology and psychology, together with Murray Stein’s Jung’s Map of the Soul and Map of the Soul – Shadow, an intriguing Jungian-accented reading of the well-known Korean BTS K-pop album by the same name and quite relevant to our discussion here: #BTS #방탄소년단 #Shadow

I am combining here my open interpretation of the Sandman-cum-Techno-Lord with Freud’s analysis of E.T.A Hoffmann’s The Sandman, that creepy man who throws sand in little children’s eyes when they do not want to (or can’t) go to sleep, and then plucks out their eyes to feed them to his children hungrily waiting in the moon. Their owl-like beaks pluck up all those severed eyes tossed in the Sandman’s bag and devour them. As the nurse in the fairy tale tells young Nathaniel:

‘He (the Sandman) is a wicked man who comes when children won’t go to bed, and throws handfuls of sand in their eyes so that they jump out of their heads all bleeding. Then he puts the eyes in a sack and carries them off to the moon to feed his children. They sit up there in their nest (platform**)**, and their beaks are hooked like owls’ beaks and they use them to peck up naughty boys’ and girls’ eyes with.’ Freud, 32

As a child I used to have a recurring dream: I was in a warehouse-like children’s dormitory with rows upon rows of children’s beds facing each other along big theatre-like aisles and corridors, which now remind me of the improvised field hospitals built to handle COVID-19 patients[3] or the uncanny rows of pods Neo glimpses when, after swallowing the red pill, Morpheus takes him to where people are kept in suspended animation so their vital fluids can be harvested to feed the AI Machine.[4]As I lay wide awake, a faceless, ominous man whose body was made entirely out of a mesh of coiling silver metallic wires would invariably appear at the left entrance to the big dormitory room carrying a burlap sack on his back, ready to place inside a child he would carry off that night never to be seen again. I could see all the children, including myself, hiding themselves under their covers to avoid being seen by the coiled wire man. But inevitably no matter how covered up I was, he would come directly after me, even though I was almost at the end of one of those interminable rows. And invariably, again, I would wake up in the nick of time, to live for another day.

I forget now when I stopped having that recurring dream, but now it is more than enough to imagine those faceless ‘sandmen’ in their coiled wire meshes in our lives as platform avatars, and hard not to see contemporary analogies where the ‘silicon sands’ and ‘smart dust’ components of the attention economy’s neuromarketing bag of tricks is eyeballing us and predictably counting on the addictive nature of screens that are basically infantilising all of us through sophisticated neural tracking techniques while picking all our collective pockets on an insidious and highly profitable daily basis. They want us to have our eyes fixated in the direction they are enticing us to look at, as in Plato’s Cave, while all the while stealthily collecting our coins and surveying our souls – a relentless unheimlich process feeding eyes, bodies and minds to the computational platform ‘moon’ nests of stock options and algorithms.

Elon Musk surveying the wreckage of SpaceX’s SN8, 10 December 2020

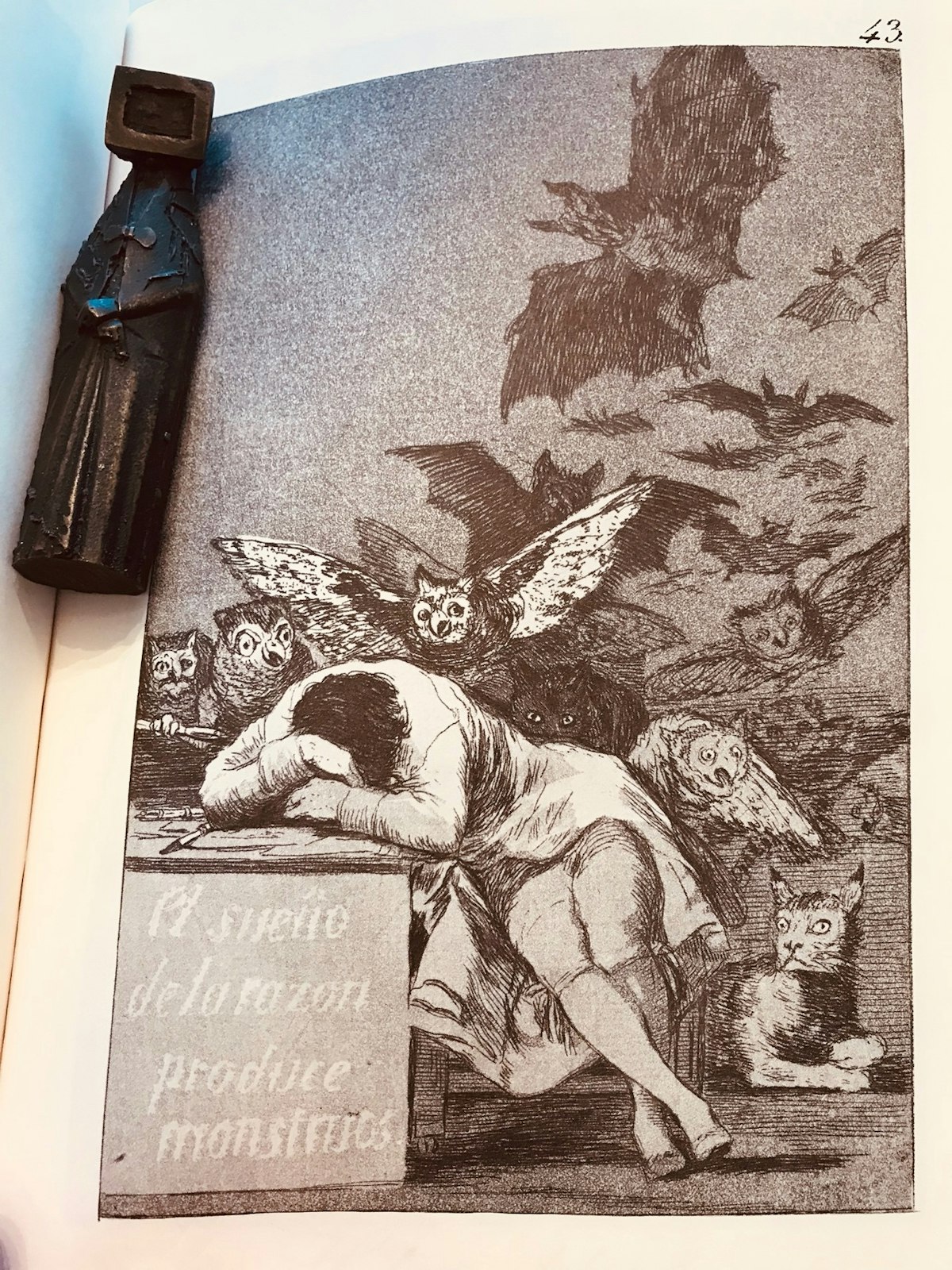

Photograph of a little bronze sculpture of a robed medieval lord with a screen for a head and Francisco Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (c. 1799), 2021

Comments